Robert Douglas Lancey

The Unlikeliest of Places

At precisely 11:50 AM on July 20th, 1941, the bell rang at Camp Takodah to call everyone around the property to the Dining Hall.

After a busy morning of chapel and classes, they had all gone back to their cabins to put on their best Takodah Blues. Staff and campers alike walked down to the center of camp while enjoying conversations about what they were doing, learning and sharing during the second session. The days were quickly ticking away, and they were already talking about coming back next year.

They entered the building, an enduring favorite on the campus, assembled around their tables, sang a song, said a prayer, and quietly sat down to enjoy a well-earned Sunday dinner. The meal was served and, while the hall was hot, the food cooked by Elsie Crowninshield was always a welcomed treat to fuel the fun of another wonderful summer.

But there was one man missing from the meal that day: a well-known cabin leader who had gained a reputation over the years as being a smart, driven, and hard-charging Takodian who took excellent care of his campers and ensured, whether they liked it or not, that they were taught as many things as they could learn in what little time they had at camp. This particular staff member didn’t report to dinner when the bell rang because he was busy preparing to continue a tradition at camp that was enjoyed in its time but has long since faded from our fields.

Robert Douglas Lancey was about to become The Bat.

He hid out in Friendship Lodge and donned a costume that made him look like a silly character from a 1930’s cartoon, complete with pointy ears, sharp teeth, piercing eyes, a short snout, a gray padded body, skin-tight leggings, wide semi-flexible wings, and a curly little tail. He laced up his classic Converse sneakers and got ready to move so fast that no one could possibly catch him.

Once Robert was ready to run, he listened for the songs sung during cleanup to finish. As he heard Uncle Oscar’s distinctive booming voice start to address the hall with various afternoon announcements, he knew that was as good as the report from a starting gun. Robert leapt out the front door of Friendship and ran around the side of the Dining Hall. He stopped in front just long enough for the campers to notice him as he waved his wings for all to see and made a quirky, squeaky “bat call.” Within a matter of moments, every single boy came bursting out of the door that was closest to his table.

As Robert took off along May Lane up towards the Brown Athletic Fields, now known as “A Field,” he could hear chairs tipping over, children yelling in excitement, screen doors banging, and Oscar laughing and hollering in approval. There were no rules to this race. The boys ran their hearts out because they knew that if they caught The Bat, they would earn a lot more than just bragging rights around their division.

They’d earn a free session of camp the following summer.

And so, they chased him at top speed around the fields and cabins. They jumped over benches and dodged trees. They crashed through bushes and ran past fire-pits. One by one, they dropped off, gave up, and watched with glee as others kept trying to grab a wing or get a hand on the head of The Bat. They hoped to tackle him and eventually figure out who it was beneath the legendary costume that was immortalized at the top of the Takodah Totem Pole.

But it was all futile. No one could catch Robert. Even though he had battled issues with breathing since he was born, he was still too fast, too good and too clever to be caught. He changed direction too quickly. He was unpredictable in his movements and yet you could tell he had it all planned out. He dashed and dodged. He twisted and turned. He zigged and zagged. Oscar would later enter into his reports that “The Bat made an appearance last week” which, as we would later learn, was his way of saying “The Bat was there but no one caught him.”

Robert, a dedicated Boy Scout with a distinctive long face and a “pug nose,” would go on to win a great many personal challenges that he faced well beyond the sanctity of a place that truly is “friendly to all.”

After graduating Columbia High School in South Orange, New Jersey, in 1938, where Robert repeatedly displayed excellence in the classroom as well as on the sports fields, he attended Syracuse University with a major in Geology and a minor in Mathematics. Robert worked at a Prudential Insurance Co. office near the school as an Actuary to help pay for tuition, books, room and board. He joined the Geology Club and Theta Tau, a co-ed professional engineering and geology fraternity with programs to promote the social, academic, and professional development of its members. He attended The Engineers’ Dances and Banquets.

In short, he was a man about town.

Robert also joined Zeta Psi, one of the oldest collegiate men’s fraternities which is “dedicated to forging academic excellence and life-long bonds of brotherhood.” He enjoyed living in the fraternity’s exclusive house at 727 Comstock Ave in Syracuse and in 1942, the year Robert received his Bachelor of Science Degree, the “Zetes” won the Colgate Sign Contest and were awarded the highly sought-after Scholarship Cup at the Interfraternity Banquet.

It was a glorious affair. Robert and his brothers enjoyed “bridge, bull sessions, and exchange dinners with the Thetas, Chi O’s, and Gamma Phi’s.”

Just before he departed school later that spring, Robert rang up an old friend named Chester Lyman Kingsbury, Jr. that he knew from Takodah. They had gone to camp together starting in 1933. “Beany,” as he went by since he was a boy, worked in his family’s well-known pressed metal toy factory in Keene, NH. He helped Robert to get a job working as a manufacturing line engineer for the summer. As domestic war production continued to escalate, and less and less steel was allowed for civilian uses, Kingsbury was forced to halt its toy production lines and made the switch to machine tools, which would help America’s factories churn out weapons and equipment for the war effort.

As the country changed before his eyes, Robert knew he couldn’t just go from job to job without facing the reality of what was happening in the world around him. The war was now global, with American and Allied forces engaged from the Atlantic in the West, across Europe, North Africa and Russia to India, China and the Pacific in the Far East. The U.S. mobilization effort was still growing, and Robert had no desire to use his gifts in science, engineering, and math just to earn a paycheck. At camp and throughout his time in school he had absorbed valuable lessons of character and the true meaning of friendship, fellowship, and fraternity. He knew it was time to make a decision – a decision that would echo for so many in the years to come.

On December 3, 1942, in Newark, New Jersey, Robert Douglas Lancey enlisted in the United States Army “for the duration of the War or other emergency, plus six months, subject to the discretion of the President or otherwise according to law.”

After 8 weeks of basic training, Robert was assigned to the 653rd Engineer Topographic Battalion, Company “A,” 10th Engineer District, where he attended various schools of instruction for training in surveying, cartography, and printing at Camp Claiborne, a U.S. Army military camp located in central Louisiana, home to the Engineering Unit Training Command. These courses were complete, and the unit certified as “deployable” in June 1943.

The thick, humid climate would prove a boon of sorts, for Robert would soon deploy to a far-off corner of the Earth he’d likely rarely thought about before.

On 16 August 1943, the 653rd departed Camp Clairborne via rail and made their way through Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and, finally, California. There the men received three weeks of combat training in the desert at Camp Anza. Robert’s last, long glimpse of the United States was of the beautiful palm trees, endless orange groves, dilapidated huts and even a little old lady, waving tearfully while crying out “God bless you boys” as the train rolled past.

Soon after, they arrived at Wilmington, the Port of Embarkation for Los Angeles. They were met at the station by Red Cross personnel who served coffee and cookies to the soldiers as they waited to board a famous old passenger liner that had carried royalty, politicians, presidents, explorers, authors, composers, financiers, philanthropists, and socialites from around the world. But those days were long since gone. Now she carried only American soldiers to their wartime deployment destinations. Owing to her high-speed, which made it very difficult for an enemy submarine to attack, she was typically unescorted at sea and thus usually alone.

She was the US Army transport ship SS George Washington.

The ship, Robert’s home for the next several weeks, was built in Stetting, Germany in 1908 and operated as a luxury liner until her confiscation during World War I. She was formerly known as the USS Catlin (AP-19) and later renamed the George Washington. She was a large, fast ship at 722.5 feet long with 36,000 tons displacement, an average speed of 15 knots, and an impressive top speed of 26 knots. She had some of the largest twin engines and boilers afloat.

The identity of each man was checked upon reaching entry to the gangplank of the George Washington. With his rifle slung over one shoulder and his “A” bag over the other, Robert’s last step on American soil was taken as he boarded the transport for his journey into the “Great Unknown,” as the men called it.

When they departed the West Coast of the United States on 6 September, Robert and his buddies initially thought they were headed for Africa since the ship was steering south toward Mexico and the Panama Canal. Suddenly, a day or so into the trip, the ship stopped, and held still for a while. The liner then resumed speed and slowly changed course to the southwest, heading towards what they assumed was Australia and the war against Japan in New Guinea. The fact is, they had never been told where they were going.

Robert loved to study the stars, as he had since he was a little boy, and his scouting days had provided a great many lessons about adaptability in the face of doubt. He cleverly used a milk bottle top and a needle from a sewing kit to fashion a compass he could use to gauge their heading and used celestial navigation to plot their trip. The Captain of the George Washington later heard about what was going on and proceeded to inquire as to what Robert and his buddies were up to. When he discovered that they had accurately determined their course and location, he not only allowed the boys to proceed with their experiments, he strongly encouraged them and confirmed their findings as they went along.

Robert and his ‘navigating crew’ kept tracking the ships’ course and soon suspected something was off. They were veering too far south for Brisbane, and maybe even Sydney, but the captain gave them no clues. The hot weather of the equator cooled and jackets and coats again made an appearance. Now they also knew there was only one place they could be headed: India.

Life, otherwise, on board the ship was extremely monotonous. They had only two meals a day with breakfast at 8 and dinner at 5. They swiped whatever else they could find from the galley, which frequently landed the men in trouble. Other than fire drills to keep them as alert as they could be out in the middle of the Pacific, Robert and the men had little to do besides loaf around on deck and review what they had learned in their training.

On 15 September, the Equator was crossed and an old maritime ceremony in honor of King Neptune was held. Ten percent of the 653rd went through the ‘Shellback initiation’ with the rest of the soldiers watching and receiving certificates formally granting them membership in the ‘Ancient Order of the Deep.’

On 29 September, George Washington arrived at the island of Tasmania. The men were granted one day’s shore leave which gave them an opportunity to “stretch their legs,” to see the sights of the island, and to meet the local inhabitants. Robert was given a warm welcome “by the people from the other side of the world.”

On 1 October, they were underway once again and arrived Fremantle Harbor, in Perth, Australia on 7 October 1943. There Robert managed to get his hands on an Australian coin which he placed into his “A” bag for safe keeping. The troop transport was resupplied, refueled, and put to sea later that same day. Owing to Japanese control of the Dutch East Indies, and the frequency with which enemy submarines and surface raiders would conduct sweeps out of Singapore and Batavia (now Jakarta), George Washington kept far to the south in the Indian Ocean, avoiding the Bay of Bengal and headed to the west coast of India. They finally reached Bombay on 20 October.

In just under two months they had covered over 16,000 miles, zig-zagged through enemy waters, experienced the heat of the tropics, and the freeze of Antarctica. They had seen all manners of seas from rough and tumble “roaring 40’s” to the calm and quiet of the Pacific. They had memorized the sounds and sensations of the ship’s mighty engines and now, as they came to a full stop at Ballard Pier, they were ready for their next adventure.

In the late afternoon of 22 October, Robert and the men of the 653rd left Bombay, now called Mumbai, and headed north on the famous Indian Railroad. The train passed through the ancient city of Ahmedabad, then took a northeast route as straight as a plumb-line all the way to New Dehli. As engineers themselves, Robert’s comrades would’ve all appreciated the construction work. As they passed Jaipur and New Delhi, the endless flat fields of Rajasthan gave way to the foothills of the Himalayan mountains. As a geologist, Robert was especially excited about this leg of the journey. The varied size and nature of the mountains appealed to him in a great many ways and he immediately became fascinated with the strange and unusual scenery. Passing into the highlands at the Ganges river gap near Jawalapur, the train skirted north and arrived at Dehra Dun, the capital of the Indian state of Uttarakhand, at 1400 on 25 October 1943.

The 653rd hopped off the train and marched to the British Royal Air Force Transit Camp, located on the other side of the city. One of the oddities to the men were the pyramidal tents that served as temporary quarters. The camp would serve as temporary work space and quarters until Base Camp Sunderwala was built about 40 miles to the northeast. That specific site was chosen because the city was the headquarters for the British-Indian government agency that made the famous Survey of India nearly 100 years earlier under Surveyor General Sir George Everest, for whom Mount Everest is named. After their equipment arrived, the men took refresher courses in mathematics, astronomy as well as road and topographical survey, before settling down to start map production work alongside British liaison officers and men.

Charles “Bob” Pitzer, a USAAF pilot who flew aerial supply routes described life on the southern flank of the Himalayans:

Living conditions in the Assam Valley were primitive. Personnel generally lived in tents or bamboo bashas [huts]. A few lived in tea plantation bungalows or in bungalow outbuildings. During the monsoon season bases were seas of mud. Sidewalks and tent foundations had to be elevated to stay above standing water. Temperatures during the monsoon season were extremely hot with very high humidity. Clothes and shoes mildewed within days. Food was government issued C-ration. Personnel did not eat off base for sanitary reasons. Malaria and dysentery were prevalent diseases. Water could be consumed only after purification by iodine.

Nevertheless, that was the beginning of “Map City USA” as they called it.

Robert, with his love of geology, hoped to see more of the mountain range, and maybe glimpse Everest itself, by taking a flight along an infamous route known as “The Hump.” The name came from Allied pilots who flew the dangerous path from airfields in northeastern India to air bases in Yunnan in southwestern China. Owing to the Japanese occupation of Burma (now Myanmar) in 1942, and the capture of Myitkyina along the Irrawady river, there was no safe Allied land route from India to China, so any troops, supplies and gold to Chiang Kai Shek’s Nationalist Government in Chungking had to come by air.

From airfields at Chadua and Dinjan in Assam, air transports flew thousands of supply missions across the eastern edge of the Himalayas into China. The sight and sound of these flights would have been a near constant companion. The 500-mile route was very difficult, given unreliable charts, few radio navigation aids and challenging, often unpredictable weather. Rain was almost constant as were high winds and the constant fear of Japanese fighters. At its highest the transports struggled over five extensive ridgelines, the tallest being the Satsung range at 15,000 feet. By the end of the war, 594 aircraft were lost on the route, with 1,659 passengers and crew killed or missing. Everyone – especially the allied air crews – was aware of the danger.

Even so, Robert would keep an eye out for a chance to take a ride and see the sights.

For the next several months, he applied his engineering skills and helped produce a wide range of maps in a region of the war that’s rarely talked about and often forgotten. The 653rd eventually produced and delivered a staggering 9,948,000 maps and related navigation sheets including target maps for the 14th Air Force, the Royal Air Force, XX Bomber Command and the Eastern Air Command. They also participated in the surveying and construction of the Ledo or “Stilwell” Road (named for Joseph W. Stilwell, the General in charge of the American effort in the China-Burma-India theater), a 1,072-mile long overland connection between India and China, which was only finished after a combined British-American-Chinese offensive cleared the Japanese from Myitkyina in May 1944.

The first ground convoy reached Kunming on 4 February 1945.

Robert’s work on the Ledo Road was of particular interest to him as it was one of the most monumental engineering projects of the war, involving 17,000 Americans and 35,000 locals building a road through mountainous jungle for over two years. The human cost was substantial, with over 1,100 American lives lost – and an untold number of local lives as well – the road was described as costing “a man a mile.”

When the end of January 1944 approached, Robert put in for some well-earned R&R.

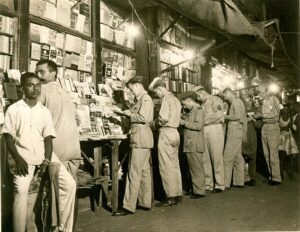

He and a friend from the 653rd, PFC Evan Rodgers Hammitt, were granted leave and permission to travel to Calcutta. That city was known by Americans for having clean military barracks, plenty of ways to relax including British military clubs and bars, and it offered a radical change from the harsh environment of the remote Doon valley. Plus, what little military pay they had went a long, long way in India.

On 27 January 1944, Robert and Evan took an RAF flight for several hours along the base of the Himalayas – marveling at the majestic mountains – from Dehradun to Chakulia Airfield, another RAF airbase in Kharagpur, India. Once they arrived, they immediately inquired about a short ‘mail run’ flight that regularly transported mail and men back and forth from Khargpur to Calcutta.

They were in luck when they discovered that an aircraft was due to depart early the next morning.

That evening, a rousing party took place well into the night with RAF air crews and, likely, American personnel as well. One man, Flying Officer Thomas William Townley, known affectionately as “Chota,” was so “full of life” that he was seen “dancing on the roof of one of the bashas.”

At 0530 on 28 January 1944, Robert and Evan boarded FD-811, a Douglas DC-3 “Dakota” flight operated by the RAF’s 31 Squadron for the Group 221 ‘Mail Run.’ They were joined by CPL Frank Lynch of the 10th Weather Squadron, and CPL Murray Jay Thorn, an American meteorologist (or “weather guesser”), along with 3 Britons from 31 Squadron travelling as passengers. The flight crew consisted of Chota, as pilot, and 3 crew members from the Royal Airforce Volunteer Reserve and Royal Canadian Air Force.

Chota was inexperienced at night flying and when the flight took off at 0600 as scheduled, the sun had yet to rise. He was also still exhausted from the celebration of the previous evening and that further strained his ability to fly. His orders were to take off, fly a brief circuit around the airfield and then proceed northeast to Calcutta.

Eight minutes later, for reasons that are still not fully known, RAF FD-811 crashed into the ground near Khargpur and burst into flames. Everyone on board, including PFC Robert Douglas Lancey, was killed.

The aircraft was still burning when the rescue crews arrived and there was no hope of survivors.

The following day, 29 January 1944, Robert was buried at 1600 in the Chakulia Army Cemetery, on the outskirts of Chakulia Airfield. His resting place, Grave 3, Row 1, Plot 2, was marked with a simple wooden cross bearing his name and rank. To his left was his friend and fellow solider PFC Hammit. To his right was CPL Thorn. CPL Lynch was also buried nearby.

Within a matter of days, word of his son’s death reached Rodney Eli Lancey in South Orange, NJ. A US Army’s Casualty Assistance Officer and Military Chaplain arrived at the house, delivered the awful news, and handed Lena Maude Celeste Lancey, Robert’s mother, a folded US Flag.

Lena would never fully recover from that day.

Rodney, however, set aside his immense personal grief and immediately set upon the work of having his son’s remains repatriated to the United States to be buried in the family plot in Townsend, Massachusetts. He also sent letter after letter for the following year working to get Robert’s personal effects returned to the family.

In early 1945, Rodney learned that Robert’s personal effects had, indeed, been sent home. They consisted of various pieces of clothing, bedding, his glasses, uniform, insignia, books, the Australian coin from Perth and a Boy Scout Mess Kit. He also had a few extra souvenirs from his adventures in India (possibly intended as gifts for his family) including multiple Ghurka ‘kukri’ knives, a brass elephant, a carved tiger and several India-themed Christmas Cards.

The reason Rodney never received the items was because they had been loaded onto the Liberty Ship SS Richard Hovey in March of 1944.

Richard Hovey sailed from Bombay on 27 March on a course for the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean, with 41 members of the merchant crew, 28 members of the Naval Armed Guard, a consular passenger and Army cargo officer, who would have been responsible for Robert’s personal effects.

At 1615 on 29 March 1944, two torpedoes fired from the Japanese submarine I-26 slammed into the Hovey’s engine room and No. 4 cargo hold causing a large explosion that rocked the ship from end to end. When a third torpedo exploded in No. 3 hold, the cargo ship began to buckle amidships and sink. Captain Hans Thorsen gave the order to abandon ship and the 70-man crew quickly escaped into lifeboats and rafts. Within moments, the Japanese submarine surfaced and started firing 5.5-inch shells into Robert Hovey with a large deck gun.

Set aflame, she slipped beneath the waves, taking Robert’s personal effects to the bottom of the Pacific.

At that point, Japanese Sailors began firing 25mm antiaircraft guns and small arms at the lifeboats, killing one Armed Guard crewmen. The rest hid in the bottom of their lifeboats or jumped in the water, taking cover behind or underneath the lifeboats and other flotsam. The submarine then rammed and sank one of the lifeboats as the Japanese continued to shoot at any Sailors seen in the water, killing another man.

Suddenly they heard the Japanese call out in clear English “Where is your captain? We want your skipper!”

Captain Thorsen stood up in boat No.1, along with three other crew members at his side. They were taken aboard the submarine as prisoners and the submarine departed, leaving the remaining two lifeboats drifting apart in the Indian Ocean. Four days later, 25 survivors were rescued by British freighter Samcalia and it wasn’t until 14 April that 38 more survivors were picked up by British freighter Samuta.

Eight months later, I-26 herself was sunk somewhere east of the Philippines.

In the winter of 1948, Robert’s remains finally came home from Plot 7, Row P, Grave 1554 at the temporary U.S. Military Cemetery near Kalaikunda Air Force Station in Kharagpur, India. After a two-month journey across the Pacific onboard the cargo ship USNS Dalton Victory (T-AK-256), he arrived at Oakland Army Base and was processed at Fort Mason in California. From there, Robert was transported by freight train to Fitchburg Station in Massachusetts and then delivered by truck to H.L. Sawyer & Co. Funeral Home. His remains were received by Funeral Director Rodney Liversage just after 5:00 PM on Monday, 20 December 1948. A memorial service took place later that week and then Robert was permanently laid to rest in Hillside Cemetery at 31 Highland Street in Townsend. A small marker added in August 1949 bears his name.

But, that’s not where Robert’s story ends.

On 12 July 1973, a massive fire broke out at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, MO, the repository of millions of military personnel, health, and medical records of discharged and deceased veterans of all branches of service throughout the 20th century. Although 42 fire districts battled the blaze for nearly 2 full days, the relentless conflagration destroyed approximately 16-18 million Official Military Personnel Files, including the records of PFC Robert Douglas Lancey.

History tried three times to wipe out Robert’s story. First, we lost the man. Then, we lost the effects. Then, we lost the records.

But history, so to speak, didn’t realize what it was dealing with.

History didn’t count on Uncle Oscar Elwell casting Robert’s name into a bronze plaque and placing it upon the fireplace of Memorial Lodge for all Takodians to see. History didn’t realize that the memory of The Bat would last for decades upon decades after Robert had made his remarkable run. History didn’t count on all of us, including you, coming together to discover and share the story of a man who only wanted to rise above his personal challenges and be all that he could be.

“The Greatest Casualty is to be Forgotten,” they say in the Wounded Warrior Project.

From this day forward, Robert Douglas Lancey shall always be remembered.

Read the next story in the series.

Return to the Lost Takodians of WWII main page.

SOURCES:

- Lancey Family interviews

- YMCA Camp Takodah History, Oscar & Francis Elwell, 1971. Takodah YMCA Archives.

- YMCA Camp Takodah Registration Cards. Takodah YMCA Archives.

- Ancestry.com Records, Media, and Lancey Family Trees

- Columbia High School in South Orange, NJ,

- Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries

- Syracuse University Student Directories 1935-1945

- Syracuse University Onondagan Yearbook, 1941

- Syracuse University Onondagan Yearbook, 1942

- Zeta Psi Fraternity

- Kingsbury Toys – Pressed Steel Metal Toys

- Keene Sentinel, 2006

- Historical Society of Cheshire County

- Fold 3 Records, Media, and Military Documents

- Newspaper Archives

- Newspapers.com

- history.army.mil

- Camp Clairborne, Wikipedia

- SS George Washington, Wikipedia

- CBI-History.com

- The Hump, Wikipedia

- Ledo Road, Wikipedia

- American Gi Life in India in World War II, Janoed.com

- A Yanks Memories of Calcutta, Clyde Waddell, 1944

- 31 Squadron Operations Records Book, RAF

- Royal Air Force Musuem, London, UK

- The National Archives (UK)

- Gov.uk

- National Archives (US)

- Aviation Safety.net

- UndyingMemory.net

- First in the Indian Skies, Norman Franks, 1981

- American Air Musuem in Britain

- RAF Commands Forum

- RAF-In-Combat.com

- ww2aircraft.net

- Newspaper clipping, Muskogee Public Library, Muskogee, OK

- Keene Evening Sentinel, 1944

- SS Richard Hovey: a Tale of Japanese Atrocities and Survival, Bruce Felknor

- Individual Deceased Personnel File, Robert Douglas Lancey, National Personnel Records Center, National Archives, St. Louis, MO

- 1973 Fire, National Personnel Records Center, National Archives, St. Louis, MO

- FindAGrave.com

PHOTO CREDITS:

- YMCA Camp Takodah Photo Archives

- Ryan Reed personal photos, 2019

- Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries

- Wikimedia

- The Daily Orange

- USMM.org

- WeAreTheMighty.com

- Digital Commonwealth

- USSGambierBay-VC10.com

- CBI-theater.com

- Twitter.com

- Worthpoint

- SS Richard Hovey: a Tale of Japanese Atrocities and Survival, Bruce Felknor

- 1973 Fire, National Personnel Records Center, National Archives, St. Louis, MO

- Navsource

- Wikimedia